More than 60% of a new homeŌĆÖs total carbon footprint is emitted before the first resident walks over the threshold. The Future Homes Hub has published an initial decarbonisation plan to tackle the issue, but will it make a difference?

For over 20 years the housebuilding sector has been challenged at regular intervals by regulations targeting carbon emission reductions from heating and lighting new homes. The latest regulatory salvo ŌĆō the upcoming Future Homes Standard ŌĆō will cut operational emissions to zero once the electricity grid has been decarbonised. Yet the carbon emissions generated by the materials and products and construction operations needed to build the homes in the first place have barely been discussed.

A handful of builders have tried to reduce the upfront carbon impacts of new home construction, but these initiatives have largely passed the major housebuilders by, even when they were trying to meet the 2016 zero carbon homes mandate which was scrapped before it could be implemented. Contrast this with the work being done by the commercial development community, which has become acutely aware of the carbon impacts of redevelopment and invested considerable effort into reusing existing buildings rather than demolition.

All this could be about to change. The Future Homes Hub, the body set up to help the housebuilding industry navigate the climate and environmental challenges facing it, has published its New Homes Sector Net Zero Carbon Transition Plan. This considers how housebuilders can reduce the carbon emissions from the construction and operation of new homes to meet the 2050 net zero target and includes an initial transition plan pathway.

The pathway reflects the impact of the Future Homes Standard, which is due out soon, leaving housebuilders with the task of reducing upfront embodied carbon as their major challenge once the standard takes effect. But what is in the plan, and is the industry on the right track?

WhatŌĆÖs in the carbon transition plan?

The plan is supported by major housebuilders including Bellway, Berkeley, Persimmon and Taylor Wimpey and housing associations including Clarion, Places for People and Platform. Working with the Carbon Trust, the plan uses estimates provided by housebuilders of carbon emissions per home in 2022 to establish a whole-life carbon baseline for an average home.

This adds up to 235 tonnes over each homeŌĆÖs lifetime, with 39% of these emissions coming from powering the homeŌĆÖs heating, lighting and appliances. That means 61% of the total carbon footprint has been emitted before the new owner walks over the threshold ŌĆō with 50% of lifetime emissions coming from the products and materials used to construct the home, 6% from construction operations and 5% from the housebuilderŌĆÖs head office and other operations.

The Future Homes HubŌĆÖs initial carbon transition plan

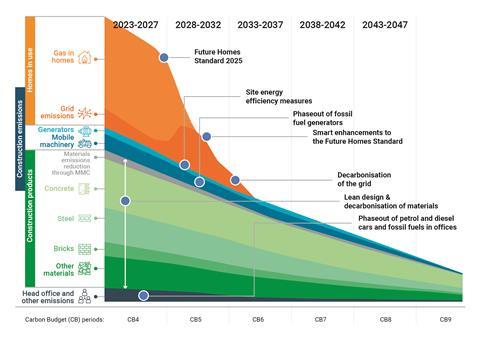

The report identifies nine decarbonisation levers including the impact of the Future Homes Standard. Others are the use of smart controls and energy storage, construction plant decarbonisation and design for low embodied carbon materials. Four of the levers are dedicated to the decarbonisation of steel, cement, brick and other materials used to build the home.

The transition plan pathway seeks to align with the governmentŌĆÖs carbon budget delivery plan, in conjunction with the climate change committeeŌĆÖs carbon budgets which include industry targets. The materials decarbonisation pathway includes the transition plans that different manufacturing sectors have set themselves.

A graphical representation of the initial transition plan shows a rapid decline in operational emissions from 2027 thanks to the FHS, with operational emissions having no impact at all by 2035 when the grid is set to be decarbonised.

The materials decarbonisation pathway is slower. The 2022 figure of 24.2 million tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2e) drops to 14.56 MtCO2e by 2035, when the grid has been decarbonised. The plan assumes these industries will not meet the net zero deadline with emissions of 4.70 MtCO2e in 2050.

The plan acknowledges the contribution of increased timber construction and MMC and assumes that this will grow by 17% for new-build houses by 2050 and 4% for apartment blocks. This will contribute a modest, 3% reduction in emissions from materials by 2035 from a 2022 baseline of zero, and a reduction of 11% by 2050. The bulk of materials emission reductions will be driven by manufacturing industry decarbonisation.

The Future Homes Hub makes it clear that the initial transition plan will change as it is subject to a range of uncertainties including shifting government policy and the actual rate of grid and materials decarbonisation. ŌĆ£What we didnŌĆÖt want to do was provide an over-optimistic, almost artificial initial transition pathway,ŌĆØ says Dan Neasham, head of homes and sustainability at the Future Homes Hub and author of the report.

ŌĆ£We wanted to take a sort of midline optimism and use best available data to inform the progress of the sectorŌĆÖs decarbonisation. What we have done in the initial version of the plan is respond as best we can to the governmentŌĆÖs carbon budget delivery plan.ŌĆØ

Neasham adds that the Future Homes Hub is establishing an embodied carbon implementation board to oversee progress of the plan, which will include government representation.

Industry reaction

So, what do those with experience of delivering low-carbon housing think of the plan? Architect Pollard Thomas Edwards (PTE) has been delivering rural, suburban and urban housing on a range of scales for many years including for major housebuilders. Tom Dollard, the firmŌĆÖs sustainability and innovation partner, warns that the plan lacks urgency.

ŌĆ£The priority at this point in time, if you want to minimise climate change, is to minimise the amount of carbon emissions going into the atmosphere in the next five to 10 years,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs not a 30-year thing; we donŌĆÖt have that much time.ŌĆØ

He says the focus must be on upfront embodied carbon, because this makes up a much greater proportion of lifetime emissions and takes place early on in the homeŌĆÖs life.

Ross Boulton, associate sustainability consultant at Buro Happold, who previously worked for Barratt South West, agrees but cautions that rapid change is difficult for the housebuilding industry. ŌĆ£I would expect to see rather more rapid reduction in embodied carbon than this [carbon transition plan] is showing, but itŌĆÖs such a difficult issue because it affects the full value chain and how contractors and developers procure all the materials,ŌĆØ he says.

ŌĆ£This goes through so many different hands and back to manufacturing and material extraction, so it is a challenge.ŌĆØ

Dollard and Boulton agree that the industry cannot wait for manufacturers to decarbonise and so should play its part. ŌĆ£There has to be effort from both sides,ŌĆØ Boulton says.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs not possible to fully decarbonise building construction without low-carbon materials and products ŌĆō and the supply chain engaging with that actively. But that doesnŌĆÖt mean to say that developers should sit back and just expect or wait for that to happen, because it is by no means guaranteed.ŌĆØ

Dollard makes the point that decarbonising heavy industry is a long, slow process.

What could the industry do differently?

Lynne Sullivan, an architect and chair of the Good Homes Alliance, points out that the report does not mention the contribution which design changes could make to reducing upfront embodied carbon. ŌĆ£My big bugbear is the thinking doesnŌĆÖt include design,ŌĆØ she says.

ŌĆ£If you design a place with wide roads and lots of hard surfaces, then ŌĆō apart from probably making it hotter ŌĆō you are going to have a much higher carbon intensity. Narrower carriageways and less hard surfacing mean you are actually designing out the problem from the start.

ŌĆ£The same thing applies to housebuilding. If you look at the standard housebuilderŌĆÖs detached house with a metre in between each one, then you can imagine how much carbon you could save if you joined them together to make a terrace. But nobody talks about that aspect.ŌĆØ

Boulton adds that eliminating basements from apartment buildings would cut emissions as these are particularly carbon intensive.

The Future Homes HubŌĆÖs Neasham counters that this was not within the remit of the report. ŌĆ£There would be impacts from shifting the typology mix,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs always going to be important to respond to the needs of a particular market and developers will be making those decisions.

ŌĆ£We can certainly inform the impact of adopting different typologies, and thatŌĆÖs something weŌĆÖll look to do. But we donŌĆÖt want to prescribe planning changes or anything like that. ThatŌĆÖs beyond the intention of the report.ŌĆØ

Pollard Thomas Edwards is working on a housing scheme for developer Untypical, a company formed from Hopkins Homes and Tilia Homes, where the ambition is to meet the 2030 upfront carbon limit set out in the Net Zero Carbon ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° Standard. The NZCBS limit for a single family home starting onsite in 2025 is set at 430kg/CO2e/m2 and drops to 290kg/CO2e/m2 for developments in 2030.

There is nothing unconventional about these homes. They will be timber-framed and built on a raft foundation, which is thicker under the perimeter walls, and screw piles instead of concrete-filled trench foundations. Other than the foundations, a key carbon saving measure is restricting the use of brick to the plinth.

A Future Homes Hub report into the embodied carbon impacts of meeting the Future Homes Standard shows that the upfront embodied carbon of a timber framed end-of-terrace, mid-terrace and detached home with a brick outer skin is only 3-5% lower than the same housing types built solely from masonry thanks to the carbon impacts of the brick outer skin and other common elements.

The PTE scheme, however, will feature three cladding options ŌĆō timber shingles, timber boarding or render over board. These have the added advantage of being lighter, which helps to reduce the size of the foundations.

Dollard says more radical options such as recycled brick and crushed stone foundations in place of concrete were ruled out because this would make getting NHBC certification more difficult.

Loose-fill hemp insulation has been used for the walls in the scheme as this has a BBA certificate. ŌĆ£Our modelling shows that we can get below 250kg/CO2e/m2 if weŌĆÖre not really trying. ThatŌĆÖs the way IŌĆÖd like to see the housebuilders go,ŌĆØ Dollard says.

ŌĆ£The biggest win is that itŌĆÖs not really much more money as we arenŌĆÖt adding technology; we are taking away material. WeŌĆÖre taking away the brick and replacing it with render, which is cheaper. The timber cladding is a little bit more expensive, but is like for like with brick.ŌĆØ

The initial transition plan predicts that the use of timber and MMC for apartment blocks will increase by just 7% by 2050. Reducing upfront carbon emissions from apartment blocks is more challenging than for houses as the blocks are usually built from concrete, with timber all but ruled out because of concerns about fire.

Buro HappoldŌĆÖs Boulton says that, other than avoiding carbon-intensive features including basements and transfer structures, making the frame more structurally efficient is the answer. This could include waffle or ribbed slabs, which use less material.

He points to one developer who has started to measure how much concrete they are using per square metre on their developments. ŌĆ£It means that you can scrutinise the efficiency of the structural design with a single figure, so you can benchmark it across different schemes,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£This is a very quick and easy way of flagging any inefficiencies early doors.ŌĆØ

Using cement substitutes is another way of reducing the carbon intensity of concrete, although there are limited supplies of ground granulated blast furnace slag and fly ash as these are the byproducts of carbon-intensive processes.

The cement industry is making efforts to decarbonise the manufacturing process. Elaine Toogood, senior director for concrete within the Mineral Products Association, makes the point that the initial pathway for concrete does not go down to zero as it does not factor in the role of carbon capture and storage (CCS).

The worldŌĆÖs first large-scale CCS plant at Brevik, in Norway, for cement producer Heidelberg Materials recently went operational, proving the technology exists, and there are plans for CCS plants in the UK.

ŌĆ£The Future Homes Hub has said that they are happy to model the route map and update it because CCS will make a significant difference,ŌĆØ Toogood says. ŌĆ£Any decarbonisation of cement and concrete needs to factor in carbon capture technology as it has been acknowledged as essential and will make a difference.ŌĆØ

How difficult is it for the industry to change?

Dollard agrees with Boulton that the complexity of the housebuildersŌĆÖ supply chains makes change a challenge and adds that, like most of the industry, they tend to be risk averse. ŌĆ£There are concerns about supply chains and scaling up [to new ways of doing things],ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£Ultimately, there is a risk-averse culture when it comes to scaling up, so they want to do what they did last time.

ŌĆ£For a brick cavity wall, they donŌĆÖt need to change their specification and can use their existing suppliers as they are happy with them. They donŌĆÖt want to have to stop to do research, pay consultants and do due diligence and meet with a [new] supply chain. Even just going to a timber frame is quite a significant change in the housebuilderŌĆÖs business model as itŌĆÖs a whole set of [new] details and supply chain.ŌĆØ

Would regulating upfront embodied carbon emissions provide the nudge needed to push housebuilders in the right direction? Dollard says they are already responding positively towards targets in local plans, for example in Cambridge and London which require whole-life carbon assessments for large schemes.

ŌĆ£If this were to become a priority, housebuilders are extremely good at hitting a target,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆØAnd theyŌĆÖll do it very cost effectively and efficiently.ŌĆØ

Next steps

The government flagged a consultation on approaches to measuring and reducing embodied carbon in new buildings when it launched the Future Homes Standard consultation back in 2023. To date nothing has materialised.

The Future Homes Hub, which is in regular contact with the government, was expecting a consultation earlier this year, but again there has been nothing. So it is down to local government intervention and industry innovation to drive change.

Neasham accepts that there should be a much greater industry focus on exploring design opportunities to reduce carbon, and that developers have a responsibility to explore different approaches to design and materials use. He stresses that industry collaboration is the key to success.

He wants data from industry initiatives such as using different materials and approaches to be reflected in an updated carbon transition plan, which is due to be published in early 2026. This will be more detailed and include carbon transition pathways for different housing typologies.

Neasham says: ŌĆ£What the updated plan will do is explore those options in more detail, and we are collecting more and more data from developers who have undertaken whole-life carbon assessments. And we are talking to the supply chain, product manufacturers and so on to understand the impact of these different products.

ŌĆ£With a better data set, we really do want to revisit this and look at different scenarios ŌĆō which will be explored in the next version.ŌĆØ

No comments yet