Immigration is shaping up to be the defining issue of 2007 ŌĆō with a huge political scrap being fought over the statistics and what they mean for the UK. But whatŌĆÖs it like on the frontline? Vikki Miller reports from Peterborough where 16,000 migrants have created the worst housing crisis in the cityŌĆÖs history. Photography by Tim Foster

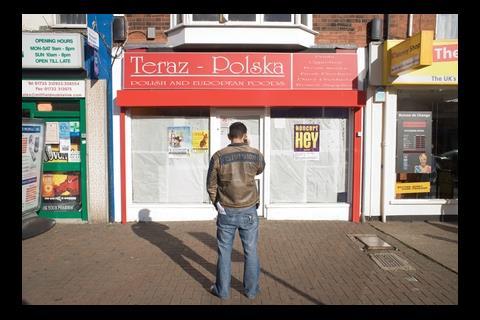

As the light fades over Lincoln Road in Peterborough, huddles of young men form on the pavement in front of the brightly lit fast food joints, internet cafes and coffee shops. Outside Budget Guest House, four teenagers smoke cigarettes and drink cans of FosterŌĆÖs. One block down, a young woman pulls the shutters down at the Work Force Plus agency and hurries into the bar next door.

Cars speed up and down the main road, windows open and music blaring. A large minibus pulls up to the curb and discharges dozens of workers in fluorescent jackets and maroon trousers ŌĆō people shipped in and out daily from the fields and factories on the outskirts of Peterborough. They chat briefly and then trudge up one of the numerous streets lined with terraced houses coming off the main road at right angles.

Inside Paulo LoureiroŌĆÖs bar on Lincoln Road, techno music booms out of the speakers. The bartender lines up shots for his Portuguese friends playing pool, while out the back young Polish women chat with friends back home on the internet. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs funny,ŌĆØ Paulo says peering out on to the street. ŌĆ£It used to be so quiet around here ŌĆō so quiet. Now itŌĆÖs very very busy.ŌĆØ

But behind the bustle, Peterborough is a city in trouble. A sudden influx of migrant workers E E the past three years has pushed public services to the brink. Peterborough has the third highest number of registered workers in the country. More than 16,000 migrants have come to live and work in the area since May 2004, when eight eastern European countries joined the EU ŌĆō a population increase of 10%. This influx, known locally as ŌĆ£the explosionŌĆØ, caught the city completely off guard. Starved of sufficient funds, public services and local amenities are struggling to meet needs.

One of the hardest hit sectors is the housing market. The city is in the midst of the worst housing crisis in its history. The councilŌĆÖs waiting list has hit an all-time high at over 9,000 applicants. Just four years ago it was 4,500. There are also more homeless people than ever before ŌĆō more than 600 last year. Many local residents blame ŌĆ£the explosionŌĆØ for the longer wait for council homes. They say the foreigners have taken their homes and get housed before local residents do.

Unsurprisingly, a closer inspection of the housing figures reveals that the proportion of migrant workers and foreigners on these lists has been at a constant 10% for at least five years. It is not outsiders who are inflating these numbers, but local Peterborough residents, people who have been living in the city for years and years. The reality is, most migrant workers have gone straight into the private rented sector ŌĆō sparking a boom in the buy-to-let market and a subsequent affordability crisis.

ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs enormous pressure on the housing market,ŌĆØ sighs Julie Rivett, housing options support team leader at Peterborough council. ŌĆ£The problem stems from the private rented sector. This is where most migrants go to be housed so these properties are being snapped up by local residents at inflated prices to let out as houses in multiple occupation [HMOs].ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£It used to be that the council used these homes to house people on the waiting list,ŌĆØ Rivett adds. ŌĆ£Now itŌĆÖs a valuable resource we can no longer tap into.ŌĆØ

Contrary to popular belief, the council does not have a legal duty to house the migrant workers. The government denied members of the eight European countries rights to housing benefits when they joined the EU in 2004, to reduce the political fallout of allowing them to work here.

HMOs are being snapped up by local residents to let out ŌĆō itŌĆÖs a resource we can no longer tap into

Julie Rivett, Peterborough council

Councillor John Holditch, cabinet member for housing at Peterborough council, is desperate to resolve the situation. Soaring property prices mean that local young couples can no longer afford to buy a home in Peterborough. Houses that used to cost around ┬Ż100,000 have risen in price by 40% since 2001. ŌĆ£These homes are being snapped up by cash buyers to convert into HMOs so the number of homes available to the market is greatly diminished. ItŌĆÖs not professional landlords coming up from London doing this. ItŌĆÖs local people,ŌĆØ Holditch explains. ŌĆ£In simple terms, people are being priced out. Now, those that wouldnŌĆÖt normally need social housing are finding themselves on the housing register, swelling the numbers.ŌĆØ

The severe shortage of homes for PeterboroughŌĆÖs growing population means that rents have also shot up. Holditch estimates that in the last two years rents have increased by at least ┬Ż100 per month for a typical HMO. The average wage in Peterborough is also below the national, and even regional, average due to the large number of low skilled jobs in the area. ŌĆ£The gap between affordability and earnings is just widening and widening,ŌĆØ Holditch says.

Housing associations are not able to offer relief, either. The four based in Peterborough ŌĆō Accent Nene, Minster, Axiom and Cross Keys Homes ŌĆō are too busy dealing with the increased numbers on the council list to take any action. Cross Keys Homes manages 10,000 homes and has recently borrowed an extra ┬Ż100m to build 1,500 homes. But chief executive Mick Leggett knows that this wonŌĆÖt solve the affordability crisis. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre full up,ŌĆØ he says, throwing his hands in the air. ŌĆ£The city is totally full. Only around 0.3% of our properties are empty here. Last year we built the largest number of homes ever in Peterborough, but only 17% of those were affordable. ItŌĆÖs just not good enough.ŌĆØ

Leggett also admits that the housing associations are not as geared up to help E E migrant workers as they could be. ŌĆ£The impact of the migrant workers has not reached our sector yet as they have all gone to private rented homes,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£But we know that they will probably come as they settle more. We have no set strategy yet but we are working on one.

ŌĆ£We need to get people working here [at Cross Keys] that speak Portuguese, Polish and Slovakian,ŌĆØ he adds. ŌĆ£No one speaks those yet apart from the cleaners. ThereŌĆÖs so much building going on in Peterborough that we should be more welcoming to the migrants, who are doing most of the construction work, so they donŌĆÖt go away again and mess up our plans.ŌĆØ

If the migrant workers were to be found homes by housing associations, they would be spread throughout the city. As it is, the majority have so far ended up in the neighbourhoods of Millfield, New England and Dogsthorpe, to the north of the city centre. These areas ŌĆō referred to locally as ŌĆ£Old PeterboroughŌĆØ ŌĆō have become ghettoes of foreigners and resentful natives.

Residents say their area has gone to the dogs. Every week without fail, Holditch receives some 30 letters from locals complaining about the HMOs. ŌĆ£They usually tell me that there are hundreds of people living in this house or that one and that we should go and investigate. Either that, or theyŌĆÖre complaining that all the foreigners have stolen their homes.ŌĆØ Holditch dutifully dispatches one of his four-strong team to investigate every complaint but, because the governmentŌĆÖs migrant figures fell far short of the reality (see box), his department is grossly under resourced.

There is no doubt that many people living in these HMOs are living in substandard conditions. Kat Chiva, a community development worker at New Link, the councilŌĆÖs asylum and migrant centre based in Millfield, has heard a constant stream of stories from clients about these appalling conditions.

ŌĆ£I am told that two or three-bedroom houses can have up to 14 people in them,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£Sometimes the landlords donŌĆÖt even convert the buildings to house more people ŌĆō they just let them pile in. I went with a client to view one house and the walls were black, it had damp,E E it stank and looked like it had never been cleaned ŌĆō and the landlord wanted ┬Ż60 per week. I wouldnŌĆÖt let my dog live in a house like that.ŌĆØ

In one house the walls were black and damp and stank. I wouldnŌĆÖt let my dog live in such a house

Kat Chiva, New Link

Still worse, migrants in Peterborough have been living in tents on the banks o f the river Nene after being thrown out of their accommodation when their work contract ran out. They were subsequently re-housed by homelessness officers.

The problem is, the council does not know how many HMOs there are in the city and so cannot control them. Landlords were obliged to register from April 2006 but so far only 200 out of an estimated 900 have done so. Earlier this week, the East of England Regional Assembly organised the first conference bringing together residents and public services, to try to improve the situation for both sides.

In an effort to get more HMO landlords signed up, Holditch and his team attempted to knock on every suspected HMO door, to find out exactly how many people were living there. ŌĆ£We didnŌĆÖt find many true HMOs,ŌĆØ Holditch admits. ŌĆ£Often there would be a large number of toothbrushes or pairs of shoes by the door but when they said not all those people lived there ŌĆō we couldnŌĆÖt argue with that. It is not a problem to the extent the public feel it is, we know that much at least. ItŌĆÖs very difficult to quantify.ŌĆØ

In an effort to appease the locals, the council asks the migrants to modify their behaviour. ŌĆ£We work very hard with the police, asking the migrants not to stand around on the streets and scare the locals,ŌĆØ Holditch says. ŌĆ£If we get a complaint from a long-term resident, we take it very seriously.ŌĆØ

The solution, Legett and everyone else working in housing in Peterborough knows, is to regenerate Old Peterborough. The neighbourhoods need sprucing up, he says, which would attract a mix of tenures and nationalities, and make them a pleasant place for everyone to live in again. But this just isnŌĆÖt feasible. Despite the HMOsŌĆÖ grotty appearances, demand has pushed house prices in the area unnaturally high. This makes it hard to attract outside private investment, Leggett explains, as well as making it too expensive to compulsorily purchase particularly shabby properties.

There is, however, plenty of private outlay at the other end of town in the Hampton district to the south of the city centre. Here, thousands of homes are being built by developers such as George Wimpey, Bovis Homes and David Wilson as part of the governmentŌĆÖs expansion plans for Peterborough. An integrated growth study report by Arup earlier this month recommended that 25,000 homes be built in Peterborough by 2026 ŌĆō around 1,300 units per year.

Rivett knows that these new homes, a large proportion of which will be for families, will only go a certain way to solving PeterboroughŌĆÖs housing crisis. A recent analysis of the housing register revealed that over 55% of applicants required a one-bedroom unit, up from around a third a few years ago. The Hampton homes are also priced well outside the migrant workers affordability range ŌĆō a three-bedroom home costs on average ┬Ż215,000.

But it is not just the lack of homes that is the problem. It is the shortfall in funding from central government to deal with the sheer number of people. Sorting out the population figures, and the corresponding funding, is HolditchŌĆÖs number one priority. ŌĆ£We canŌĆÖt plan services because we donŌĆÖt know who weŌĆÖve got here,ŌĆØ he laments. ŌĆ£The problem has been there have been so many so fast. And coaches arrive here every day direct from Poland full of people. I see it with my own eyes. ItŌĆÖs out of control and our services canŌĆÖt cope. WeŌĆÖre the ones working on the ground. We know how hard it is.ŌĆØ

How many migrants?

Nobody really knows how many migrant workers there are in the UK. The Home OfficeŌĆÖs recent embarrassing back pedalling ŌĆō revising their figures from an initial 800,000 to 1.5m ŌĆō was seen as a victory for town halls, which have long complained that they are not receiving sufficient funds for the real number of migrants using their public services. Local council grants are based on national census figures and many of the new migrants, particularly those who move on within a year, are not reflected in annual cash allocations.

The Local Government Association demanded a ┬Ż250m contingency fund earlier this month from the government to cope with the increasing pressure on public services. At the time of going to press, communities secretary Hazel Blears had agreed to a ┬Ż50m fund to manage cohesion and integrate services.

G Rafal Demczuk, deli owner, Polish

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖve lived in England for 11 years now and IŌĆÖve just opened the first Polish-owned deli in Peterborough. DonŌĆÖt get me wrong ŌĆō there are loads of Polish products in other shops, but they are mostly owned by the Pakistani community. None of them are owned, run and staffed by Polish people.

In my opinion, the Asian community are the main people catering for Poles in Peterborough. They are more in tune with our economic reality. They stock our food goods, give us insurance, assign contracts for building work and organise our transportation.

Some of the Polish people live in appalling conditions here. Much, much worse than if they were in Poland. Sometimes you can only get in and out of the bathroom through the kitchen, which is totally unhygienic. There is also extreme overcrowding and properties can be sub-let four or five times over. We refused to allow our shop manager to live any longer in her house and helped her find a new one. Most of the homes are owned by the Asian community.

The building regulations in this country are also weaker than in Poland. When we bought this shop, we had to spend ┬Ż15,000 to get it into shape. We brought our labour over from Poland, because it was cheaper and then got a British company to check the work at the end.

IŌĆÖm not saying the Polish havenŌĆÖt caused any trouble at all. There have been incidents of drink driving, as the approach to it here is very different to Poland.

I have also lived in Slough and there is definitely less antagonism here but maybe that will change when our shop is fully opened. We will have to wait and see.ŌĆØ

G Kat Chiva, community development officer, New Link Asylum and Migration Service, Polish

ŌĆ£When I first started working at New Link it was very different. We dealt a lot with refugee and asylum cases but since the eastern European countries joined the EU, the services have had to change dramatically in a short period of time.

We need a different set of languages ŌĆō not as many Arabic speakers, but more Polish ŌĆō and thereŌĆÖs also different issues. It used to be about immigration rights but now itŌĆÖs more practical ŌĆō for example, how to get a national insurance number.

There is no doubt there is a lot of exploitation going on. People working in agriculture or for gangmasters are often on minimum wage with no national insurance and paying no taxes. I would say about 90% of the people are on minimum wage, but there is also a strong black market. People are also obliged to take low-level accommodation with their job. If they decide to quit, they lose their home too. People are too scared to report a lot of the mistreatment they receive.

The HMOs are also a huge problem. This has been the major trouble with integration with the local community. The local residents are upset that their neighbourhoods are being trashed, and rightly so. The migrant workers didnŌĆÖt learn at first how to use the bin systems, there were cars parked all over the roads and there was a lot more noise on the streets.ŌĆØ

G Paulo Loureiro, bar owner, Portuguese

ŌĆ£I came to Peterborough four years ago from Lancashire because I had relatives here. The Portuguese came to the city before the Polish. The local people think the Polish will take their jobs. They are afraid of what will happen and there is not much integration. To be honest with you, I can see why they feel like that. If you were here, following the rules correctly and then people came along who were not respecting the rules ŌĆō driving cars without a licence, having no insurance, drink driving ŌĆō youŌĆÖd be angry too. ItŌĆÖs not racism ŌĆō just a desire to live a peaceful life. The Polish need to follow the rules more.ŌĆØ

Source

RegenerateLive

No comments yet